One of the frustrations of the hyperactive shutterbug (me) is what to do with yourself after and before the ‘magic hours’, e.g., an hour or so after sunrise until an hour or so before sunset. My answer: near infrared (IR) photography. Apart from special circumstances (including desperation), we would normally avoid shooting images with the sun directly overhead, but it turns out that this is the optimal time for recording (IR) images. The images included in this entry demonstrate the absence of haze and rich tonality that attracts folks to the approach, but do not include any really vivid examples of Wood Effect, in which greenery acquires curiously light tones due to the reflection of IR light from foliage. It’s Utah in the dead of winter, there is no foliage!

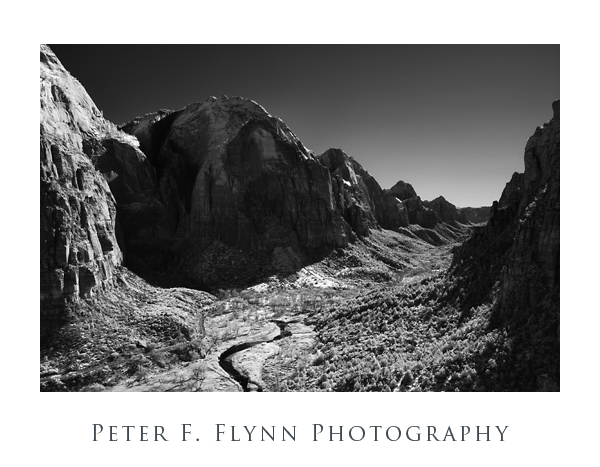

The image above, looking south down the canyon of Zion NP was recorded on January 18, 2009 at around 15:40 MST using the Nikon D200 converted to IR capture (see below) and the AF-S DX Zoom NIKKOR 12-24mm f/4 IF-ED lens at 24mm. Exposure was f/16 at 1/13s, ISO 100.

The image above, looking south down the canyon of Zion NP was recorded on January 18, 2009 at around 15:40 MST using the Nikon D200 converted to IR capture (see below) and the AF-S DX Zoom NIKKOR 12-24mm f/4 IF-ED lens at 24mm. Exposure was f/16 at 1/13s, ISO 100.

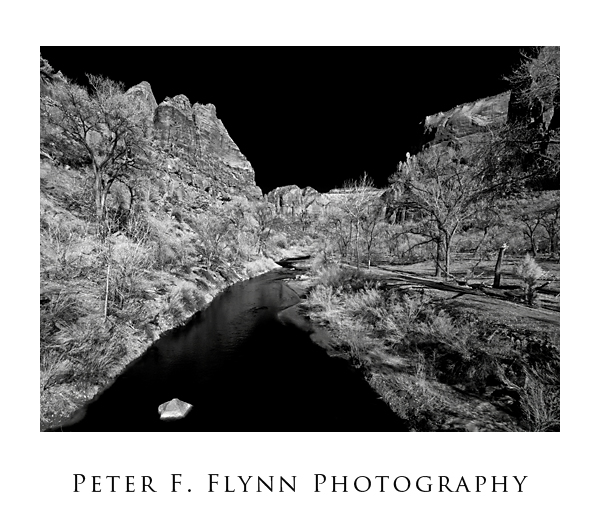

The image above of the Virgin River in Zion Canyon NP was recorded on January 18, 2009 at around 13:50 MST using the Nikon D200 converted to IR capture (see below) and the AF-S DX Zoom NIKKOR 12-24mm f/4 IF-ED lens at 18mm. Exposure was f/16 at 1/40s, ISO 100.

The image above of the Virgin River in Zion Canyon NP was recorded on January 18, 2009 at around 13:50 MST using the Nikon D200 converted to IR capture (see below) and the AF-S DX Zoom NIKKOR 12-24mm f/4 IF-ED lens at 18mm. Exposure was f/16 at 1/40s, ISO 100.

There are several ways to gear up for IR photography, and the method I chose was to send in my underused Nikon D200 digital SLR for IR conversion. Digital sensors have high sensitivity to electromagnetic energy all the way from below 400 nm to about 1200 nm. To avoid all sorts of trouble, an IR filter is placed over the sensor to block IR infiltration on the image. IR conversion involves replacing the IR filter with a visible light filter. The two most popular filters have visible light cut-offs at either 720 nm; which allows a bit of visible light (red) to pass through, like the Wratten 89B filter; or 830 nm, which renders a black and white image with greater contrast and tonal range than you can obtain with the 720 nm rig. I chose the 830 nm filter set up, which is approximately equivalent in frequency response to the Kodak Wratten 87C filter. The conversion was done by Life Pixel Infrared Conversion Services*, of Mukilteo, WA. It’s not particularly cheap at $375, but the folks at Life Pixel did an excellent job – no apparent dust left on the sensor during conversion and they also set a custom white balance. All-in-all I believe it is an excellent value. The turn around time for the conversion was about ten days.

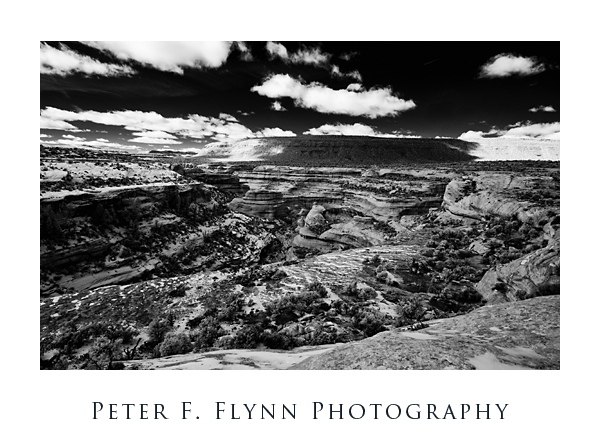

The image above of Sipapu Bridge in Natural Bridges NM was recorded on February 14th, 2009 at about 13:30 with the Nikon D200IR and the AF-S DX Zoom-NIKKOR 12-24mm f/4 IF-ED lens at 18mm. Exposure was f/16 at 1/13s, ISO 100.

The image above of Sipapu Bridge in Natural Bridges NM was recorded on February 14th, 2009 at about 13:30 with the Nikon D200IR and the AF-S DX Zoom-NIKKOR 12-24mm f/4 IF-ED lens at 18mm. Exposure was f/16 at 1/13s, ISO 100.

There are a number of excellent photographers working in the IR. Included are:

Reha Akcakaya : http://rehaakcakaya.com/

Stephen R. Brown: http://www.srbphoto.com/infrared/index.html

Kenneth Farmer: http://www.infraredvideo.com/

Laurie White Hayball

Cyrill Harnischmacher

Chris Maher#: http://dreamsofthegoddess.com/

Joeseph Paduano: http://www.joepaduano.com/

Fredrik Rasmussen: http://www.momentcorp.com/

Martin Reeves: http://www.thehiddenrealms.com/

Patrick Rice: http://www.ricephoto.com/abtpatrick.htm

The following websites are also worth visiting:

Digital Photography For What It’s Worth: http://www.dpfwiw.com/ir.htm

Infrared Photography Buzz: http://irbuzz.blogspot.com/

Infrared Photography Forum: http://www.irphotoforum.com/

…and there’s a lot more out there…

*I am directing you to the image comparison page to avoid the very informative but slightly annoying voice-over index page.

#Some nudity, but tasteful.

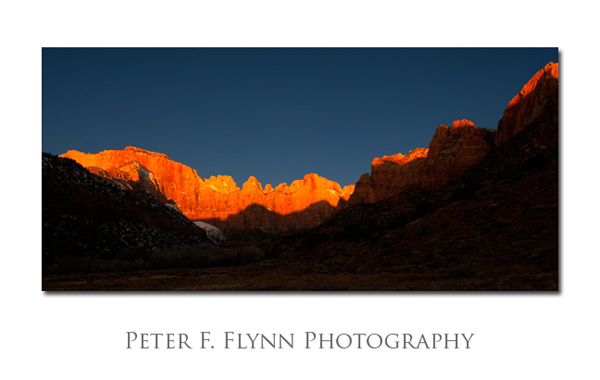

The Towers of the Virgin at dawn are arguably the most excellent scene in

The Towers of the Virgin at dawn are arguably the most excellent scene in